I remember I was eight or nine years old. Daddy had dropped Mammy, my little sister and me to the train station, to get the train down to Cork. We were coming here. I was wearing a new summer dress. It was so pretty – a pastel flower pattern. It was my first time to wear it. I’d been saving it for a special occasion and this was it. As we waited for the train, I squatted down and sat on my hunkers on the platform. Not realising that the hem was caught under the heels of my sandals, I stood up again as the train approached. I heard the fabric tear. I was horrified. My gorgeous dress ripped across the back, along the hem. I felt so sad. Something had been done that couldn’t be undone. I wished I could turn the clock back just a few seconds. The next week, my dress was mended, but the line where it had ripped and been restitched remained, visible if you knew what to look for. To an onlooker, it might have seemed like a trifling thing. But I never forgot that dress and that instant when I ripped it.

Category Archives: memory

74. Like summer holidays past

The rain fell sideways as we packed the car this morning. Mammy had moved the car to as close to the door as she could get it. Still, we swopped bags of food and our mini suitcases for water and leaves trailed into the house underfoot.

It was a tight squeeze, five of us and all our stuff filling up the boot and obscuring the rear window. I remember rainy Saturday mornings just like this, in the early 1980s, Daddy hoisting the suitcase, the wind break, the deck chairs, onto the roof rack of the Ford Escort, covering the lot with the blue tarpaulin from an old tent, securing it with rope.

I had the playlist ready for today’s drive to Cork – 80s hits, of course, that we sang along to in between bursts of conversation.

The rain continued – sporadic heavy showers – and wind buffeted the car sideways. We pulled in to the Rock of Cashel for lunch – ham sandwiches made from yesterday’s boiled ham and Brennan’s bread washed down with sweet black tea from a flask. We stood around the picnic table in the rain, the hoods of our raincoats up, as a sudden heavy shower chased away the slash of blue sky that had briefly appeared. I couldn’t have been happier. Few things in the world taste as great as ham sandwiches and tea from a flask on a wet day, memory and nostalgia adding magical flavour to the food.

We reached our destination late afternoon and quickly unpacked the car. My sister started to make dinner and realized she was two ingredients short. Lily and I walked the couple of hundred metres up to the shop in the village square. On the walk back, we were blown down the hill by the strong wind, rain hitting us on the back. ‘This is perfect,’ I said to Lily. A seaside holiday in Ireland isn’t complete unless you get at least one wild night like this.’ The wind, the rain, the slight bite in the air, took me back 30, 40, 45 years, to family vacations here in west Cork, in Kerry, in Wexford, in Mayo.

Tomorrow we plan to go to the beach – in our raincoats, most likely.

73. Squeezing the last drops out of summer

Autumn is definitely here. It’s raining more and it’s colder. We lit the fire in the kitchen yesterday. And still, the girls and I remain in Ireland, squeezing every last drop out of this long long summer. In the eleven years we’ve lived in Spain, we’ve never been away this long. Usually, we’d be back by now, going to the pool after our mid-afternoon siesta, or taking the dog down to the dog friendly beach in Isla Cristina.

Yet, here we are, still in Ireland, and one final adventure awaits before we return to Spain. Tomorrow morning, we are driving down to west Cork for a week in Roscarbery. It’s one of my favourite places in Ireland – a picturesque village by the sea, with an amazing beach, great walks – a simply lovely place. Because my aunt, uncle and cousins live there, we’ve been visiting Roscarbery since I was a small child, so it is infused with memories from so many different stages of my life.

Our bags are packed, the makings of the picnic are in the fridge, and we’ll be ready to hit the road after breakfast tomorrow. Forecast? Autumn showers and autumn temperatures. It’ll be lovely.

68. Worse, not better.

Around the clock, the cars whizz by. Breaking the 80km/h speed limit by 20, 40, 60km/h. Early morning is bad – commuters late to work, or timing their commute to perfection only by driving at high speed. You hear them coming at great distance, then drowning out all other sounds as the rush past, leaving a trail of noise in their wake. Sometimes, they overtake each other outside the house – a car doing 120km/h overtaking one doing 100km/h on this narrow little road. Once the commuters have passed, it’s the turn of the lorries. Great, hulking lorries, with ‘Long Vehicle’ signs on the back, made for roads much bigger than this one, they too going at or above the speed limit – lorry after lorry carrying triple, quadruple decks of frightened pigs to the slaughter house a mile farther along the road, or taking goods and supplies to who knows where. Then it’s the commuters again – going in the opposite direction at the end of the day. And then night comes and it’s the racers – joy riding at unimaginable speeds – speeds that I don’t want to imagine. A couple of nights ago, a car stopped in front of the house. It was 9:30 and I hadn’t yet closed the curtains. Odd, I thought. We’re not expecting anyone. Then I thought maybe it was waiting at the bottom of the narrow hill to let an oncoming vehicle pass. But it wasn’t that either. The driver revved and revved and revved the car and then shot away up the road like a bullet. The noise was deafening. I waited for the sound of a collision – with another car, or with the old tree on the bend in the road up at Smith’s house; my heart pounding.

We used to live our lives on this road. Cousins my age lived in the house across the road and in the house down the road; so, as kids, we were constantly going between the three houses. On summer evenings, we’d tie a skipping rope to the gate and stretch it out across the road. Daddy would stand for hours turning the rope, while us kids jumped til it got too dark. Every twenty minutes or half an hour, we’d have to make way for a car to go past.

From an early age, I walked or rode my bike the two miles from home into town, never giving a minute’s thought to my safety because the traffic was limited and no-one drove fast. When I was 12, and started secondary school, I rode my bike, alongside my cousins, to school every day, just like Daddy rode his bike to work every day, and my aunt Lillie and uncle’s Tom and Gerry rode their bikes out to Ballygibbon regularly. The road belonged to the people, not to the cars.

The road was a place for animals too. Our farming neighbours regularly herded their cattle or sheep along the road from one field to another and, on Thursday mornings, farmers from farther afield would herd their livestock down the road towards the cattle mart. We walked our dogs along the road, often not on leads, never giving a moment’s thought to their safety. Lassie, the black labrador my parents gave to me as a puppy for my fourth birthday, got into the habit of crossing the road over to Betty’s house every day for a slice of bread.

There was the summer of 1992, the year of the Barcelona Olympics, when my friend Niamh came to visit from Kilkenny. We wondered how fast we could run, compared to Linford Christie. We measured out 100metres on the road and my neighbour timed us. While Niamh ran her 100m in a handy 12 seconds, I came in at 22 seconds! I wasn’t built for speed!!

I remember a few times in the late 1990s and early 2000s, with my friend Gavin or with Julian, walking the two miles home from the pub in the dead of night. On those nights, with no lights to guide us, I worried only that I might twist my ankle in a pothole or along the side of the road. Meeting traffic was never a major concern.

Not much has changed on this road in the 52 years that I have known it. The signs have improved a bit and the surface on the bridge over the River Boyne is definitely better. Apart from that, it remains the same. The road is as narrow as it always was, with sporadic road markings at best. The same houses line the road – only two new houses have been built in the past 50 years – each house home to succeeding generations of young couples raising their children to adulthood.

The only thing that has changed on this road is the traffic. The road no longer belongs to the people or to the animals. To leave the house now, we must go by car, because it is too dangerous to walk or ride a bike. To walk her dogs, Mammy has to load them into the car and drive them to somewhere else where it is safer to walk. Even driving the car out onto the road is nerve-wracking, as drivers speed up and down the road with little thought for the inhabitants of the houses they pass. Impatient drivers occasionally honk their horns or dangerously overtake when we slow down to turn into the driveway or pull in to open or close the gate. There’s no stopping on the road for a friendly chat with a neighbour in a passing car.

Because of the traffic, the neighbours see less of each other, simply because they stay well away from the road. It’s sad and infuriating to see my lovely townland torn apart by the very road that once brought us all together. Is this progress? I don’t think so.

64. Ballygibbon

‘My surname is Walsh,’ I hear a man with an American accent tell the librarian. I’m at Edenderry library, supposedly working, but the conversation going on behind me distracts me. The man tells the librarian that his family came from somewhere around Edenderry, but he doesn’t know where. ‘There’s a place called Walsh Island a few miles from here,’ the librarian tells him, but then admits that she’s not from here and doesn’t know much about local history. She offers to go get one of her colleagues who is from here.

At this point, I can’t stop myself. ‘Excuse me,’ I say, getting up from my desk and walking over. ‘I couldn’t help but overhear your conversation.’ I could help, of course, if I was less nosy. ‘I might be able to help you out a bit,’ I tell the man. The librarian leaves us to it, while she goes off to gather up an armful of local history books that might be of interest to him. He and I start talking and, within a couple of minutes, I’ve invited him to come sit at my desk, because I feel we might have a lot to talk about.

He tells me his people are from Georgia, by way of other places in the US that I wish I had paid attention to – Indianapolis, maybe, or Indiana? And did he mention New York? He’s here with his half-brother, who is English. The two were unaware of each other’s existence until a few years ago (the English brother a war-time baby) and now the two are here tracing their roots. While the American brother is here in the library, the English brother is up at the parish office, looking at the parish records of births, deaths and marriages.

‘Have you been to Walsh’s bridge?’ I ask him, and tell him that the Walsh family lived in a house by the bridge. I know of three brothers – Pascal was my science teacher at school, Andy is an auctioneer, and John recently deceased. He tells me he’s met some Walshes, has looked at headstones in the graveyard in Monesteroris and went knocking on doors at houses he thought once belonged to Walshes. His phone rings and he answers it. It’s Andy Walsh, the very man I have just mentioned, who tells him that his son is interested in genealogy and might be able to help him out.

When the call ends, he tells me that he and his brother have been here for a few days and are leaving tomorrow and they haven’t confirmed any relationships with the places or the Walshes they’ve met. I ask him where they’re staying. He tells me they’re at an AirB&B called Rushbrooke, a few kilometres outside of town. The name rings a bell and I’m pretty sure it’s a house near my house. ‘Who owns it?’ I ask. ‘Young guy. Arthur,’ he says. ‘Can’t remember his surname.’ He rings Arthur. ‘What’s your surname?’ he asks. ‘Arthur Stones,’ Arthur replies.

I almost do a comical forehead slap. ‘Arthur Stones is a distant relative of mine,’ I tell him. ‘He lives down the road from me. My grandmother and Arthur’s great-grandmother were first cousins.’ He shows me a photo of Rushbrooke, where he and his brother are staying, and now I know exactly what house it is. ‘It’s Billy Mather’s house,’ I say. ‘Up Mather’s lane.’ This is no more than 500 metres from my house, up the lane from Arthur’s home (which, coincidentally, is the house my grandmother grew up in).

Mr Walsh (I can’t believe I didn’t catch his name) opens the folder he’s carrying. He shows me photos from 150 years ago and then produces a most remarkable document. A photocopied letter sent from an aunt in Ireland to her niece in America in 1925. The niece is Mr. Walsh’s paternal great-aunt or great-great-aunt. What is so remarkable about this letter is the sender’s address: Ballygibbon.

Ballygibbon is where I come from. Ballygibbon is where Arthur Stones comes from. Ballygibbon is where Rushbrooke House is situated. And, in the back of my mind, I remember that, when my father was young, before Arthur Stones owned Rushbrooke, before Tim Mann owned Rushbrooke, before Billy Mathers owned Rushbrooke, it was owned by the Walsh family. This can’t be real!!

I phone Mammy and ask her if she can remember which house up Mather’s Lane was originally Walshes. She narrows it down to two possibilities. I phone my cousin Colette, holder of so much family and local lore. Colette is on holidays in Lanzarote and can’t say for sure which house it is.

I turn to my laptop and the 1901 and 1911 census. I search Kildare, Ballygibbon West, and there they are – the entire Walsh family – the brother of the man who emigrated to America and who Mr Walsh is directly descended from. There he is, Patrick Walsh, with his wife and six children in 1901 and with four adult children in 1911 – the other two likely married and moved away. One of the female children is the author of the letter that Mr Walsh is holding in his hands.

As the realisation dawns, we are both giddy with excitement. Through a complete coincidence, a random search for an AirB&B in Edenderry, these two long-lost brothers are staying in the very house their great-grandfather lived in and left for America in the 1850s. ‘You’re searching the wrong records,’ I tell him. The brothers have been looking for evidence of their family in County Offaly (King’s County, as it was then) and in Edenderry parish. But Ballygibbon is across the border in County Kildare and in Balyna Parish.

I phone Balyna Parish office and Fr. Maher answers the phone. The parish secretary is away on holidays. He tells me that Mr. Walsh needs to email the secretary and she will see what she can dig up in the parish records. But, he says, the records don’t go back very far, so she might not find much. I assure Mr. Walsh that they go back at least until 1918, having done a bit of digging around into my own family a few years ago. Fr. Maher suggests that the brothers go to Carrick cemetery, the most likely location of the Walsh family graves.

Mr. Walsh packs up, we shake hands and say goodbye. I assume that’s the end of it, but half an hour later he’s back, this time with his brother. He wants to take photos of all the census information I found on my laptop. I end up drawing a map of Ballygibbon and showing them who lived in all the various houses over the years. The brothers head off to do some headstone detective work at Carrick graveyard.

It’s hard to believe this happened today. That, on the very last day of their trip to Edenderry, this man should come into the library, and I should overhear him, and he should show me, by chance, a letter, and the address on that letter should be my townland, and I should trawl back through my memory to something my father had told me about neighbours of ours when he was young, and I should find a trace of them online, and they should live in the very house that this man is now staying at, owned now by a distant cousin of mine!

Isn’t life full of wonder and possibility!

59. Discovering Ireland

If you love board games, may I recommend Discovering Ireland or its cousin, Discovering Europe. I’ve been playing this with my friend Niamh since we were both in university. It was as much fun more than 30 years ago as it is now, playing it with our kids.

The object of the game is for each player to get to five towns and then exit by a port, while each player tries to block everyone else from reaching their destination and getting rid of all of their cards.

We’ve played it three times this summer so far. It generally leads to great outbursts of laughter, occasional spilled drinks, impromptu song compositions. And the kids learn a little geography into the bargain!

I really need to add it to our board game collection at home in Sanlúcar.

58. The Irish Wake Museum

So culturally embedded are our death rituals that they are honoured and commemorated in a museum in Waterford city, The Irish Wake Museum. I didn’t know this museum existed until I walked past it a couple of days ago. How could I not take a trip inside?

Housed in an early 15th Century alms house in the heart of Waterford, the museum explores Ireland’s funeral rituals from pre-Christian times, through the Vikings and up to the present day.

It was easy to see how memorial objects from the 1400s – commemorative pendants, coins and jewellery have been transformed into the memorial cards of the dead that are given out today.

I was familiar with the origins of the wake and many of the rituals surrounding it. The two or three days of sitting with the dead to ensure they really were dead. The liminality of the wake, when clocks are stopped (literally), mirrors are covered to prevent the spirit of the deceased from getting trapped, and when there is much socialising and, despite the circumstances, merriment. In certain parts of Ireland, keeners were brought in; women who performed highly ritualised keening (from the Irish ag caoineadh – to cry) over the body.

I learned that women were generally the ones who prepared the deceased for the wake because, on account of their ability to give birth, women were more able to defy death.

I learned that, in the old days, the drinking and socialising at wakes so concerned the Catholic church that notices were put up stating that unmarried young men and women who were unrelated were not allowed to be in attendance at a wake from sunset to sunrise!

It was heartwarming to see our death rituals so faithfully rendered and retold, sharing this part of our culture with visitors and instilling a sense of pride and belonging in those of us for whom this is a living and evolving tradition.

54. My bedroom

I don’t know who was the first person to sleep in this bedroom and I don’t know who will be the last. But it was mine for a while and I’m back in it again for a few weeks. I don’t know if my great-grandparents slept in it or died in it; I don’t know if my father and his siblings were born in it. But I know it’s history from 1942 onwards.

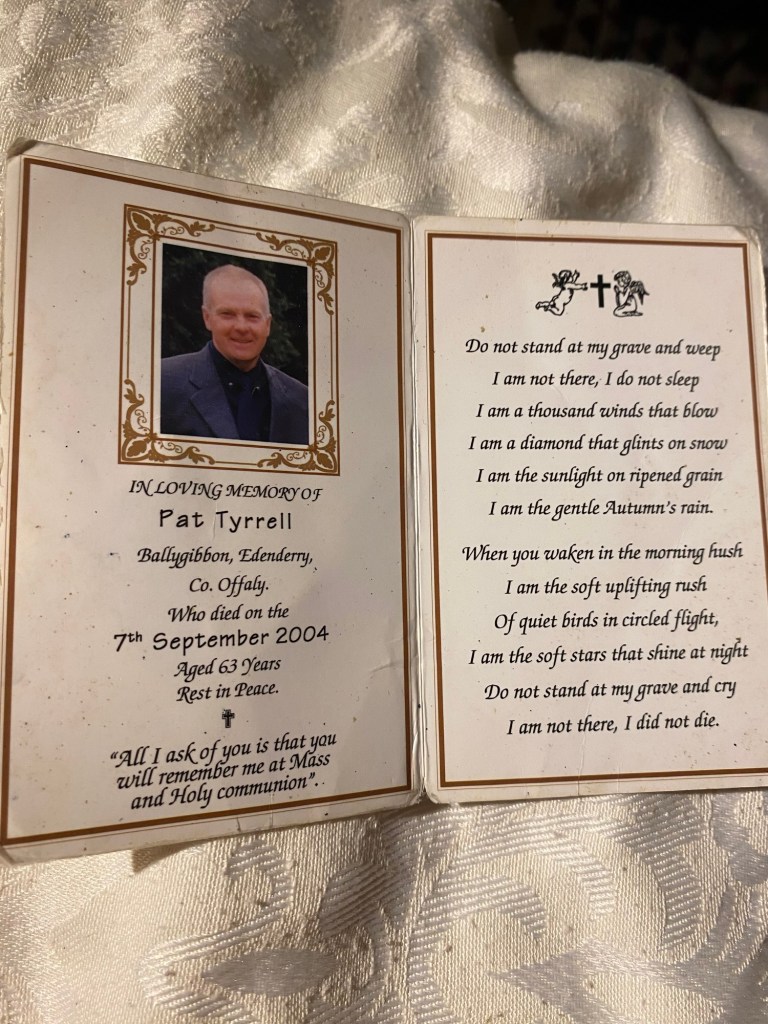

Years ago, my uncle Willie told me that his father (my grandfather), Michael Tyrrell, had spent his final months in bed in this room. Willie, Jimmy and Cissie, the three oldest children, helped their mother look after their father through his cancer and he died in this room on 31 March 1942, Daddy’s first birthday.

When I was a child, there were two beds in this room. Hard to imagine now, given how small it is. Nana slept in the double bed by the window and L-shaped to her was Cissie’s smaller bed. As a child, I slept with Cissie a lot. I have memories of that time – of Mammy bringing me breakfast in bed of a fry-up of rashers, sausages, egg, tomatoes and Nana’s soda bread. I remember crying in pain with toothache in that bed too and Mammy bringing me up aspirin or some other pain relief.

Did I stay in that bed after Cissie got sick? I don’t remember. When I was four, a new bedroom was built onto the house. It was supposed to be for me, but I never slept in it. It was too far away from where everyone else was at night, so I stayed with Cissie.

Cissie died from breast cancer when I was six and, for a while, I slept in the bed with Nana. But I didn’t like sleeping with her – I remember she had scratchy toenails! After some time, a new plan was devised. Mammy and Daddy moved up to the room that had been built for me and my sister and I slept in two single beds in what had been my parent’s room. Now Nana had the small bedroom to herself. Cissie’s bed remained there for a few years, but was eventually removed.

In May 1985, Nana died in bed in this room. I remember our cousin Betty, who lived across the road, coming over to clean and prepare the body for the wake. Nana was laid out in the bed. I had turned twelve only a few days earlier and she was only the second dead person I had ever seen (Betty’s father, Garrett, had died the previous year and I’d seen him laid out in his bed across the road). For two days, people visited the house, filing into the bedroom to pay their respects, before coming down to the kitchen or sitting room for tea and beer and endless ham sandwiches and cake.

By the time I was 12, I was well and truly fed up with sharing a room with my seven year old sister and about two weeks after Nana died, I asked my parents if I could have her room. Going to sleep for the first time in a bed so recently vacated by my dead granny felt a bit weird, I have to admit, but I soon got used to it and transformed it into my own space.

The walls of this room throughout my teenage years were covered with posters. I had huge posters of one of the space shuttles, of an F16 fighter jet (thanks to Top Gun), and of an environmental quote from Chief Seattle. There were posters and newspaper clippings of Boris Becker (little did we know!!), Bruce Springsteen, James Dean and so many more – I can’t even remember now. The room was filled with library books, Jackie annuals, and back issues of Smash Hits and National Geographic. There were mementos of the few places I had been in my life, a desk that I rarely used because it was too small and wobbly (I did my homework and studying at the kitchen table). I had my own radio too. It was in this room that I first heard about the hole in the ozone layer (it scared the shit out of me), about Chernobyl (ditto), and where I listened to endless pop music.

I stayed in this room until I left for university and returned to it at weekends and holidays, and then on visits home from Japan, Nunavut, Scotland. I moved back into it again in the summer of 2004, when I came home from Aberdeen to be with Daddy in his final weeks or months (weeks, in the end, but I wasn’t to know that then).

These days, it’s Mammy’s room and has a feeling of warmth and relaxation about it, with the comfiest bed that’s ever been here. I’m sleeping in it while I’m here. I wake in the morning and here I am, once again, in this bedroom where I’ve probably spent more nights than in any other one place in my life; in this bedroom that has witnessed so much of my family’s life.

49. Breakfast

Breakfast is generally the most perfunctory of meals. Quick and practical at the start of the day. On Saturday or Sunday, I like to make pancakes or waffles, which we eat lazily with multiple mugs of tea. But still, it’s the meal that, most of the time, I make and eat at home. I always imagine going out for breakfasts, but I’ve never lived anywhere that’s had much in the way of breakfast options.

Visiting a city is always a great opportunity for sampling breakfasts of all sorts. The memory of New York and Toronto diner breakfasts make me drool even now, and I still get nostalgic about breakfasts in Paris, Sydney, Honolulu, Vienna, London, Sevilla. Eggs, bacon, pancakes, mueslis, yogurts; breakfasts of all shapes and sizes; enjoyed with friends or in my own.

This morning, on the way through Derry, I had one such memorable breakfast. Not at a diner or a cafe, but at a friend’s house, made all the more delicious for the care and devotion my friend’s brother and sister put into making it.

The dining table was dressed with food, like that Christmas scene in Greta Gerwig’s Little Women. Eight of us sat around a table laden with rashers, sausages, black pudding, grilled tomatoes, fried potatoes, baked beans; potato farls, brown bread, toast, brioche buns, pancakes; jams, honey, marmalade, maple syrup; tea, coffee, hot chocolate. Every breakfast I love, all there on the table. I could have sat there all day, gorging myself like the Prince Regent.

Alas, we had to get on the road. Home beckoned. So, with a tummy full of food made with care and passion, I set out, another memorable breakfast to fuel my future nostalgia.

47. Ukaliq

In late 2000, I’d already been working as a volunteer teacher at Levi Angmak Elementary School in Arviat, Nunavut, for some months. Kip Gibbons, one of the teachers who had befriended me, offered to show me how to sew my own mittens. She sent me to the Northern Store to buy ukaliq (arctic hare) fur. I duly went a couple of evenings later and bought two ukaliq skins. On Saturday, I went around to Kip’s house and we sat on her floor, where she helped me to cut the pattern and showed me how to stitch the parts together.

I’ve never been much of a crafts person, so I was delighted to be making my own mittens. It was probably -20C or -25C as I walked the snow-covered streets back to my house a few hours later, proudly wearing my new mittens. I would wear them for years, and still have them today, although there isn’t much call for them in southern Spain.

On the Monday after I sewed the mitts, I wore them to school. In the school foyer, I met Peter 2 Aulajoot, an older teacher, who was always friendly and jokey with me. He chuckled when he saw my mitts. I hadn’t cut them badly or sewed them poorly. But Peter 2 noticed something that I hadn’t. While the fur on my left mitt was mostly white with a little smattering of black, the fur on my right mitt was mostly black with a little smattering of white. They looked completely mismatched. How could I not have seen this?

From that day on, Peter 2 always called me Ukaliq – arctic hare. A few other people picked it up too, but it wasn’t a name I was commonly called. But I liked that name for myself. I’d always loved hares, always got a thrill when I’d see them in Ireland. Now that I was in Nunavut, I saw them more often – including one that lived out past the reservoir and seemed as tame as a pet bunny.

I’ve carried that name – Ukaliq – with me ever since, making the frisson of excitement I feel whenever I see a hare all the sharper. So, yesterday when Michael said, ‘There’s the hare,’ I immediately turned to the window. And there she was. At the base of a granite outcrop beside the house, ears up, alert. She paused, nibbled at a hind paw with her teeth, hopped along and then sat, ears back, looking out over the sea.

I was in a state of awe and nostalgia and joy all mingled together, remembering Peter 2 and Kip and that ukaliq by the reservoir and the person I was twenty-five years ago.