At Christmas 1989, I was 16 years old and in my final year of secondary school. In February, I would have to complete my application for university – a centralized system in which I would have to list my choice of institutions and courses from one to ten. In June 1990, I would sit the state Leaving Certificate exam and, in August, I would be offered the highest ranked of the ten courses for which I had gained sufficient accumulated points in my Leaving Cert.

Geography and English were my favourite subjects and I imagined I would do a degree in those two subjects, become a teacher, and then come home to Edenderry and teach for the rest of my life. I didn’t know any better. My teachers were my role models for what could be done with a university degree. I loved Geography, ergo, I would become a geography teacher.

But, while at 16, I couldn’t imagine a life for myself outside of Edenderry, in my mind, I was a citizen of the world. From the age of 11, I’d had pen-pals in Singapore, Australia, Malawi, Egypt, Hong Kong, Spain, Greece (by the way, to this day I’m still friends with Aileen in Singapore and Haitham in Egypt), and spent vast amounts of time – and pocket money on stationary and stamps – telling them all about my life and learning all about their lives. And, shortly after I’d turned 16, I made the difficult decision to stop buying Smash Hits every fortnight and instead save up my pocket money and birthday and Christmas money to subscribe to National Geographic. I’d sit at the kitchen table or lie on my bed here in Ballygibbon, and read National Geographic from cover to cover, even the ads, as the words and photos took me on journeys to places and peoples in lands far from my little corner of Co. Kildare.

That Christmas of 1989, my aunt Marian and uncle Jim came up from west Cork to stay at Nana’s house in Gilroy. We saw them two or three times a year, but this time was a little different. Jim was a primary school headmaster and my parents had asked if he could help me with Maths. The Leaving Cert was only six months away and Maths was, by some measure, my worst subject. Poor Jim, he did his best but, he was fighting a losing battle from the start. Not only was I bad at Maths, I refused to even try to be good. My stubborn mental block took years to shift and it is residually still with me today.

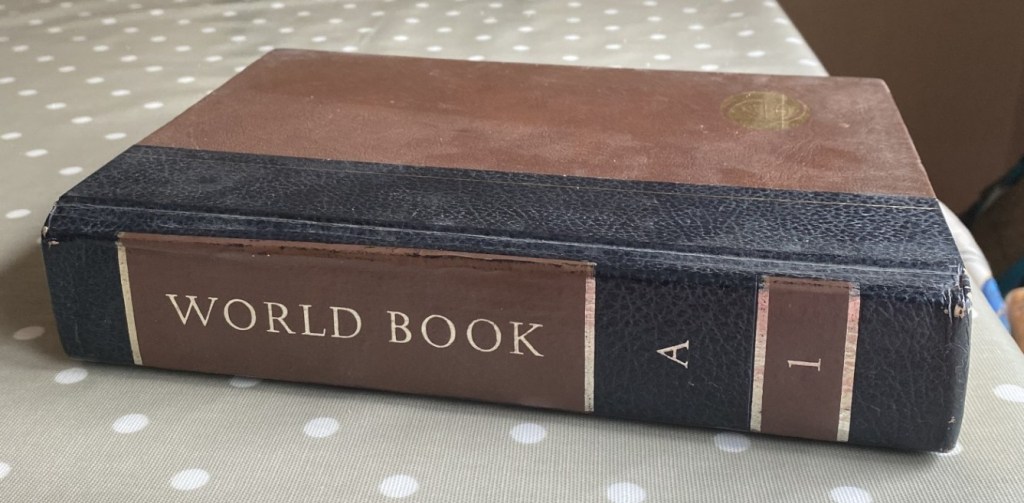

Jim, in his spare time, was also a door-to-door encyclopaedia salesman. On the day they arrived at Nana’s house that Christmas, Mammy and I popped in to visit. ‘Come out to the car,’ Jim said to me. ‘I’ve something for you.’ Out we went. He opened the boot of the car and fished out the A book of the World Book encyclopaedia. I was delighted with this and spent the remainder of the visit at Nana’s house browsing through the pages.

At home that evening, I sat on my bed, a mug of tea on the bedside table, and poured over the A book, page by page. It was filled with all sorts of interesting A things – from Kareem Abdul-Jabbar to Alexander I, from Antarctica to Austria, from Airplane to Audio-visual Materials. And then I came to page 509: Anthropology.

What on earth? There’s this field of study that I’ve never heard of before, that’s combines some of the bits I like best about geography, and that’s all about learning about people who live far away in other parts of the world. Could I do that? It seemed highly unlikely.

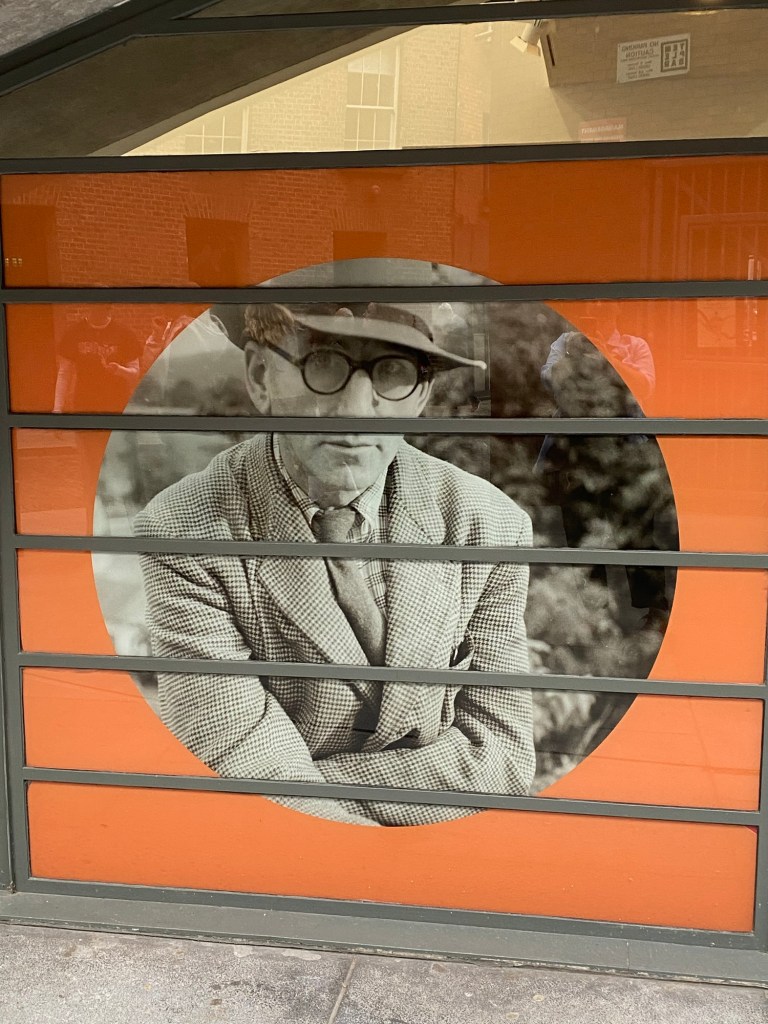

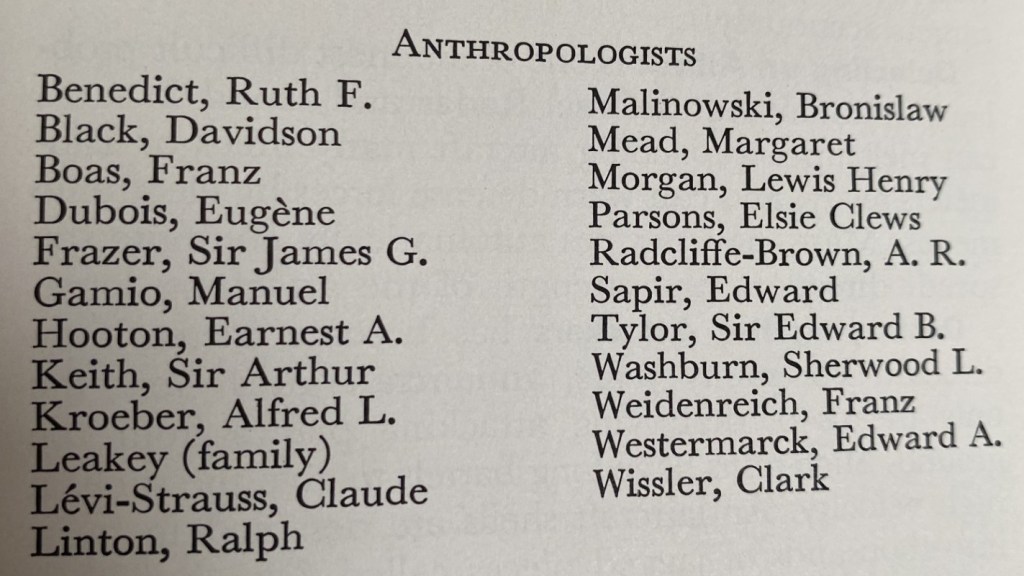

I read and re-read the four and half pages about Anthropology. Among the most renowned were a handful of women – notably Ruth Benedict, Margaret Mead, Elsie Parsons.

And I read that anthropologists did their research by immersing themselves in the lives and cultures of the peoples they studied, learning skills and languages, and then theorized and wrote about what they had learned from those experiences. Surely there were no anthropologists in Ireland! This was far too exotic and exciting!

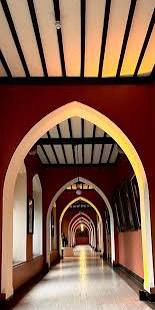

I thought about anthropology all through the Christmas holidays and, as soon as I the January term started, I made a bee-line for the school career guidance counsellor, convinced that she would tell me she had never heard of this subject or that the nearest place I could do it was somewhere in England. Imagine my surprise when she told me that the only Anthropology department in the Republic of Ireland was in Maynooth – my nearest university! How could this be? How did I not know?

In February, I filled in my university application form, still erring on the side of Geography and English in UCD, but with Arts in Maynooth as my second choice. When I received my Leaving Cert results in August 1990, I knew I had enough points to do Anthropology and Geography at Maynooth.

And did I get my degree and return to Edenderry to become a Geography teacher? Well, I got my degree. And I followed that with a Masters degree in Anthropology. Then I went to live in Japan for three years. Then I moved to the Canadian Arctic. Then I did a PhD in Anthropology, immersing myself for long periods of time in an Inuit community on the west coast of Hudson Bay. Then I worked as an Anthropologist-Geographer in geography departments in Cambridge, Reading and Exeter universities. All thanks to my uncle Jim handing me the A book out of the boot of his car two months before I applied for university.

I was sitting at the kitchen table here in Ballygibbon earlier today. I glanced up towards the bookcase and saw the A book, still sitting there. Coincidentally, today is also the day when tens of thousands of students across Ireland receive their Leaving Cert results. I hope their lives are as unexpected and serendipitous as mine has proven to be up to now.