I don’t know who was the first person to sleep in this bedroom and I don’t know who will be the last. But it was mine for a while and I’m back in it again for a few weeks. I don’t know if my great-grandparents slept in it or died in it; I don’t know if my father and his siblings were born in it. But I know it’s history from 1942 onwards.

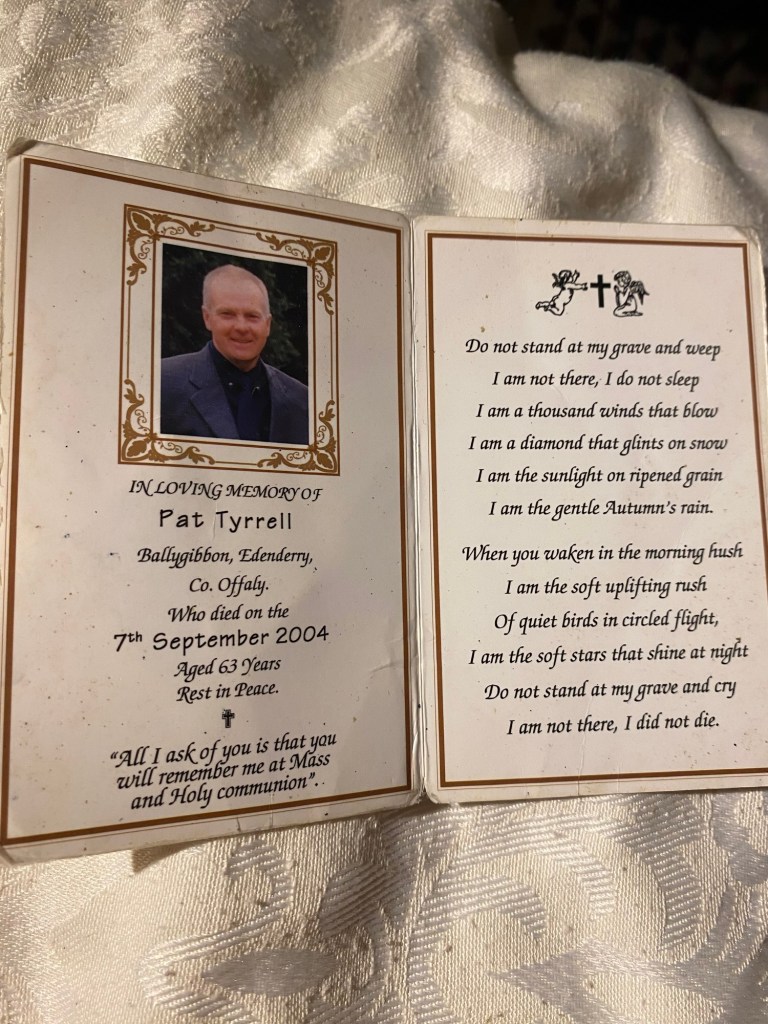

Years ago, my uncle Willie told me that his father (my grandfather), Michael Tyrrell, had spent his final months in bed in this room. Willie, Jimmy and Cissie, the three oldest children, helped their mother look after their father through his cancer and he died in this room on 31 March 1942, Daddy’s first birthday.

When I was a child, there were two beds in this room. Hard to imagine now, given how small it is. Nana slept in the double bed by the window and L-shaped to her was Cissie’s smaller bed. As a child, I slept with Cissie a lot. I have memories of that time – of Mammy bringing me breakfast in bed of a fry-up of rashers, sausages, egg, tomatoes and Nana’s soda bread. I remember crying in pain with toothache in that bed too and Mammy bringing me up aspirin or some other pain relief.

Did I stay in that bed after Cissie got sick? I don’t remember. When I was four, a new bedroom was built onto the house. It was supposed to be for me, but I never slept in it. It was too far away from where everyone else was at night, so I stayed with Cissie.

Cissie died from breast cancer when I was six and, for a while, I slept in the bed with Nana. But I didn’t like sleeping with her – I remember she had scratchy toenails! After some time, a new plan was devised. Mammy and Daddy moved up to the room that had been built for me and my sister and I slept in two single beds in what had been my parent’s room. Now Nana had the small bedroom to herself. Cissie’s bed remained there for a few years, but was eventually removed.

In May 1985, Nana died in bed in this room. I remember our cousin Betty, who lived across the road, coming over to clean and prepare the body for the wake. Nana was laid out in the bed. I had turned twelve only a few days earlier and she was only the second dead person I had ever seen (Betty’s father, Garrett, had died the previous year and I’d seen him laid out in his bed across the road). For two days, people visited the house, filing into the bedroom to pay their respects, before coming down to the kitchen or sitting room for tea and beer and endless ham sandwiches and cake.

By the time I was 12, I was well and truly fed up with sharing a room with my seven year old sister and about two weeks after Nana died, I asked my parents if I could have her room. Going to sleep for the first time in a bed so recently vacated by my dead granny felt a bit weird, I have to admit, but I soon got used to it and transformed it into my own space.

The walls of this room throughout my teenage years were covered with posters. I had huge posters of one of the space shuttles, of an F16 fighter jet (thanks to Top Gun), and of an environmental quote from Chief Seattle. There were posters and newspaper clippings of Boris Becker (little did we know!!), Bruce Springsteen, James Dean and so many more – I can’t even remember now. The room was filled with library books, Jackie annuals, and back issues of Smash Hits and National Geographic. There were mementos of the few places I had been in my life, a desk that I rarely used because it was too small and wobbly (I did my homework and studying at the kitchen table). I had my own radio too. It was in this room that I first heard about the hole in the ozone layer (it scared the shit out of me), about Chernobyl (ditto), and where I listened to endless pop music.

I stayed in this room until I left for university and returned to it at weekends and holidays, and then on visits home from Japan, Nunavut, Scotland. I moved back into it again in the summer of 2004, when I came home from Aberdeen to be with Daddy in his final weeks or months (weeks, in the end, but I wasn’t to know that then).

These days, it’s Mammy’s room and has a feeling of warmth and relaxation about it, with the comfiest bed that’s ever been here. I’m sleeping in it while I’m here. I wake in the morning and here I am, once again, in this bedroom where I’ve probably spent more nights than in any other one place in my life; in this bedroom that has witnessed so much of my family’s life.