‘My surname is Walsh,’ I hear a man with an American accent tell the librarian. I’m at Edenderry library, supposedly working, but the conversation going on behind me distracts me. The man tells the librarian that his family came from somewhere around Edenderry, but he doesn’t know where. ‘There’s a place called Walsh Island a few miles from here,’ the librarian tells him, but then admits that she’s not from here and doesn’t know much about local history. She offers to go get one of her colleagues who is from here.

At this point, I can’t stop myself. ‘Excuse me,’ I say, getting up from my desk and walking over. ‘I couldn’t help but overhear your conversation.’ I could help, of course, if I was less nosy. ‘I might be able to help you out a bit,’ I tell the man. The librarian leaves us to it, while she goes off to gather up an armful of local history books that might be of interest to him. He and I start talking and, within a couple of minutes, I’ve invited him to come sit at my desk, because I feel we might have a lot to talk about.

He tells me his people are from Georgia, by way of other places in the US that I wish I had paid attention to – Indianapolis, maybe, or Indiana? And did he mention New York? He’s here with his half-brother, who is English. The two were unaware of each other’s existence until a few years ago (the English brother a war-time baby) and now the two are here tracing their roots. While the American brother is here in the library, the English brother is up at the parish office, looking at the parish records of births, deaths and marriages.

‘Have you been to Walsh’s bridge?’ I ask him, and tell him that the Walsh family lived in a house by the bridge. I know of three brothers – Pascal was my science teacher at school, Andy is an auctioneer, and John recently deceased. He tells me he’s met some Walshes, has looked at headstones in the graveyard in Monesteroris and went knocking on doors at houses he thought once belonged to Walshes. His phone rings and he answers it. It’s Andy Walsh, the very man I have just mentioned, who tells him that his son is interested in genealogy and might be able to help him out.

When the call ends, he tells me that he and his brother have been here for a few days and are leaving tomorrow and they haven’t confirmed any relationships with the places or the Walshes they’ve met. I ask him where they’re staying. He tells me they’re at an AirB&B called Rushbrooke, a few kilometres outside of town. The name rings a bell and I’m pretty sure it’s a house near my house. ‘Who owns it?’ I ask. ‘Young guy. Arthur,’ he says. ‘Can’t remember his surname.’ He rings Arthur. ‘What’s your surname?’ he asks. ‘Arthur Stones,’ Arthur replies.

I almost do a comical forehead slap. ‘Arthur Stones is a distant relative of mine,’ I tell him. ‘He lives down the road from me. My grandmother and Arthur’s great-grandmother were first cousins.’ He shows me a photo of Rushbrooke, where he and his brother are staying, and now I know exactly what house it is. ‘It’s Billy Mather’s house,’ I say. ‘Up Mather’s lane.’ This is no more than 500 metres from my house, up the lane from Arthur’s home (which, coincidentally, is the house my grandmother grew up in).

Mr Walsh (I can’t believe I didn’t catch his name) opens the folder he’s carrying. He shows me photos from 150 years ago and then produces a most remarkable document. A photocopied letter sent from an aunt in Ireland to her niece in America in 1925. The niece is Mr. Walsh’s paternal great-aunt or great-great-aunt. What is so remarkable about this letter is the sender’s address: Ballygibbon.

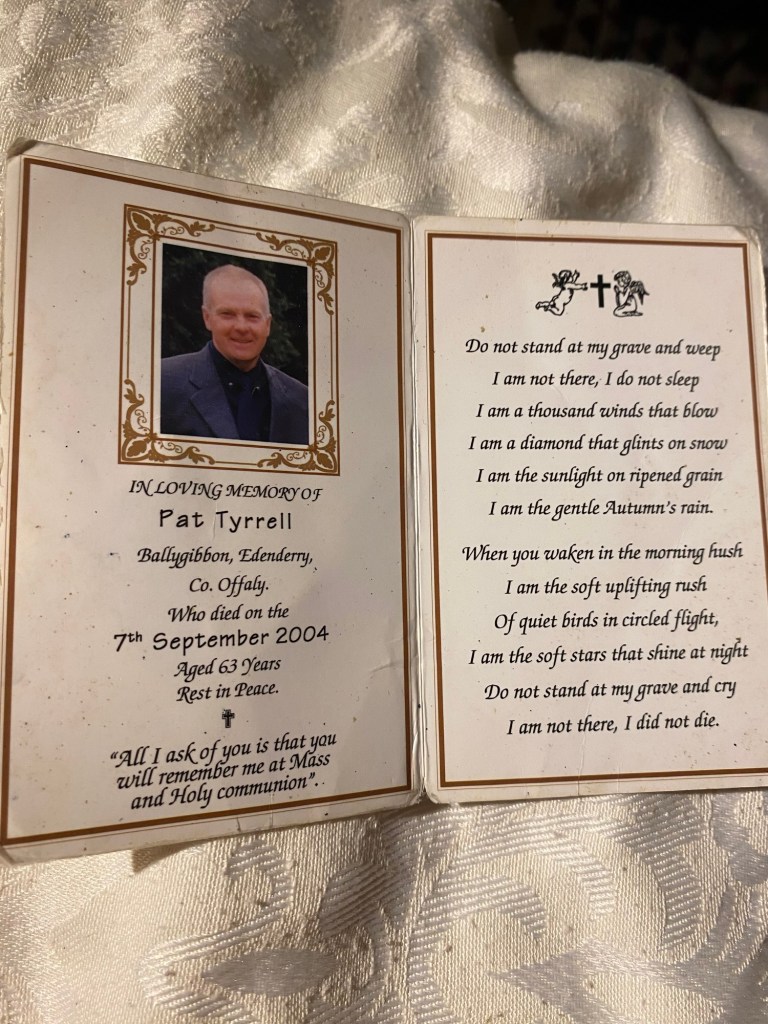

Ballygibbon is where I come from. Ballygibbon is where Arthur Stones comes from. Ballygibbon is where Rushbrooke House is situated. And, in the back of my mind, I remember that, when my father was young, before Arthur Stones owned Rushbrooke, before Tim Mann owned Rushbrooke, before Billy Mathers owned Rushbrooke, it was owned by the Walsh family. This can’t be real!!

I phone Mammy and ask her if she can remember which house up Mather’s Lane was originally Walshes. She narrows it down to two possibilities. I phone my cousin Colette, holder of so much family and local lore. Colette is on holidays in Lanzarote and can’t say for sure which house it is.

I turn to my laptop and the 1901 and 1911 census. I search Kildare, Ballygibbon West, and there they are – the entire Walsh family – the brother of the man who emigrated to America and who Mr Walsh is directly descended from. There he is, Patrick Walsh, with his wife and six children in 1901 and with four adult children in 1911 – the other two likely married and moved away. One of the female children is the author of the letter that Mr Walsh is holding in his hands.

As the realisation dawns, we are both giddy with excitement. Through a complete coincidence, a random search for an AirB&B in Edenderry, these two long-lost brothers are staying in the very house their great-grandfather lived in and left for America in the 1850s. ‘You’re searching the wrong records,’ I tell him. The brothers have been looking for evidence of their family in County Offaly (King’s County, as it was then) and in Edenderry parish. But Ballygibbon is across the border in County Kildare and in Balyna Parish.

I phone Balyna Parish office and Fr. Maher answers the phone. The parish secretary is away on holidays. He tells me that Mr. Walsh needs to email the secretary and she will see what she can dig up in the parish records. But, he says, the records don’t go back very far, so she might not find much. I assure Mr. Walsh that they go back at least until 1918, having done a bit of digging around into my own family a few years ago. Fr. Maher suggests that the brothers go to Carrick cemetery, the most likely location of the Walsh family graves.

Mr. Walsh packs up, we shake hands and say goodbye. I assume that’s the end of it, but half an hour later he’s back, this time with his brother. He wants to take photos of all the census information I found on my laptop. I end up drawing a map of Ballygibbon and showing them who lived in all the various houses over the years. The brothers head off to do some headstone detective work at Carrick graveyard.

It’s hard to believe this happened today. That, on the very last day of their trip to Edenderry, this man should come into the library, and I should overhear him, and he should show me, by chance, a letter, and the address on that letter should be my townland, and I should trawl back through my memory to something my father had told me about neighbours of ours when he was young, and I should find a trace of them online, and they should live in the very house that this man is now staying at, owned now by a distant cousin of mine!

Isn’t life full of wonder and possibility!